Guest blog post by music historian and performer, Anna O’Connell.

This year at the Cleveland International Piano Competition will mark the debut of a new exciting feature: Piano Transcriptions!

Before the advent of recording technology, how did consumers of classical music hear their favorite melodies from symphonies and operas at home? At the piano keyboard, of course! Picture that you are with your friends—think a Jane Austin setting—enjoying an evening dinner party. Dessert is over, and you head to the parlor for some music. Someone sits at the piano, and begins to play a symphony, originally composed for an orchestra. After that is over, maybe the pianist is joined by another person, and together they will play a piano four-hands (see our previous blog) arrangement of an opera overture of Mozart, or a Haydn Symphony. In Cosima Wagner’s journals, reminiscing about life with her husband Richard Wagner (of Ring Cycle opera fame), she mentions many such occasions, and how Wagner would make and play these arrangements himself!

In order to arrange or transcribe orchestral music for the piano, Wagner and other composers would reduce every instrument sounding in an orchestra into notes playable by the two hands of a pianist (or the four hands of two pianists). Composers would do this to investigate how a piece by an earlier composer was constructed or to bring a new character to a previous work, paying homage to the original composition, but also inserting the character of the later composer. In certain cases, such as the German Requiem by Johannes Brahms, the composer made a reduction of the orchestral part for piano four-hands, such that this large-scale work could be performed by a choir without the access to a full orchestra.

Reductions and transcriptions also became a form of popular consumption: composers could re-work the music of other composers and sell sheet music for piano in their own edition, with their own spark of creativity stamped upon an earlier work. We can also consider the changing instruments of the orchestra from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century. Some popular works, like Handel’s Messiah underwent huge transformations in the hands of Mozart or Haydn, both of which added and arranged parts for woodwinds that hadn’t yet existed in Handel’s day. As the classical composers added instruments to the baroque orchestrations (essentially filling in the musical tones and sounds of a later orchestra into an earlier scaffolding), they also participated in the baroque tradition of reducing larger orchestral works to the keyboard. This we can trace back through composers such as Jean Baptiste Lully, whose opera arias and dances in the late 1600s were often reimagined as harpsichord works. In addition, scholarship points to the earliest transcriptions for the keyboard as early as the 1530s.

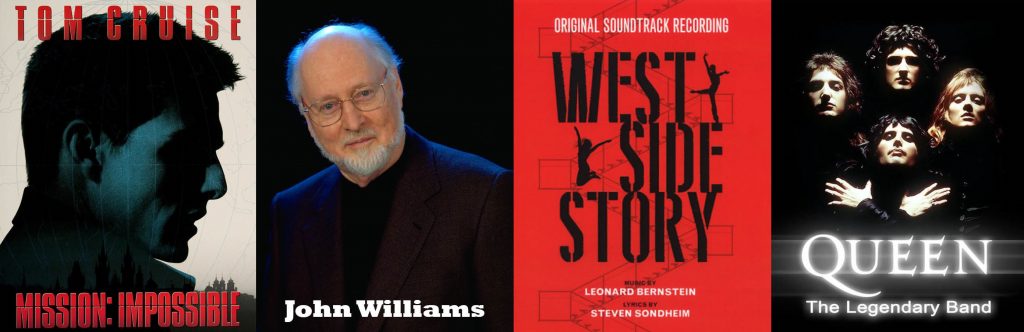

This rich history of arranging and transcribing pieces of music written for other instruments or ensemble types is in part why we are so excited to be bringing piano transcriptions to the Cleveland International Piano Competition. In our Semi-Final Round, during the Solo Recital, contestants will be asked (in addition to at least one piece by Chopin, Brahms, Schubert, or Schumann) to perform one of four virtuosic transcriptions of popular music, transcribed by Moscow-based pianist and composer Alexey Kurbatov. These four iconic melodies, drawn from musical theatre (“America” from West Side Story), film and television (“Olympics Theme” by John Williams and “Mission: Impossible Theme” by Lalo Schifrin) as well as the much beloved song “Bohemian Rhapsody” by Queen, were transcribed into piano works specifically for CIPC, and were arranged with the vast history of piano transcription in mind: virtuosic transcriptions of virtuosic music, performed by virtuosic pianists. We hope you will enjoy hearing these melodies through the new and exciting voice of Kurbatov and our contestants!